Introduction

Natural Language Generation (NLG), is a field of artificial intelligence (AI) that aims to transform data into information. It can enrich your dataset through data reduction and summarisation, or through data growth and supplementation. Imagine never having to hire an intern again. NLG adoption is rapidly increasing, primarily in the field of financial reporting, but today I will be discussing how it could potentially be utilised by chatbot technology to enrich training data sets and increase a models intent detection capabilities.

You may be more familiar with NLG in this context than you think. Remember back when you were doing English homework in school and you had to ask your ma for another word for <insert word here> to avoid repeating yourself and make your answer sound better. Or remember that time you were writing a paper in college but found it really hard to avoid plagiarism because wikipedia just phrases this so perfectly? Well this is similar to the problem faced by the brave souls who spend their days building, training and testing chatbots. Take a simple use case - building a bot that can answer questions about vehicle prices and house rental prices. First we need a dataset (utterances) to train our model, this is a group of sentences to associate with a certain intent. For example if the user says what price is this home - we would want to link this to a home_data intent, and send back some home data information, or maybe trigger an email to send a brochure etc.

So lets use the following dataset as our initial training data.

I want a big car

My friend here would like a motorbike

what price is this home

what does this home cost

Awesome, surely this covers all possible scenarios…

Testing with Rasa

To test out the dataset lets launch an ec2 instance and install Rasa. I used a medium instance, but you can get away with using something smaller if you’re just experimenting. The following steps should get an instance of Rasa up and going for you. Unless you decided to use CentOS instead of Ubuntu, in which case you are on your own.

sudo apt install python3-pip

sudo apt update

sudo apt install python3-dev python3-pip

pip3 install -U pip

pip3 install rasa

pip3 install rasa[spacy]

rasa init

We append our new intents and utterances to the out of the box Rasa project. This project has some simple intents such as greeting, goodbye and are_you_a_bot. We then split the dataset into a training set and a test set - you can probably guess from the names, but we’ll train our model using the training set and test our dataset using the test set.

rasa data split nlu

cp data/nlu.yml data/nlu_original.yml

mv train_test_split/training_data.yml data/nlu.yml

rasa train

rasa test --nlu train_test_split/test_data.yml

At this point it’s all looking positive on the command line, the test command should spit out a confusion matrix indicating that all of our intents were identified correctly. The ins and outs of confusion matrices, accuracy, recall and f1 are outside the scope of this blog, but to put it simply -

- The confusion matrix represents detected intents v expected intents

- Accuracy represents how confident you are that when you predict an intent, you’ve made the correct prediction

- Recall represents how confident you are that you can identify every instance of a particular intent in a dataset

- F1 represents the balance between Accuracy and Recall

If you inspect the intent report in the results folder, the precision and recall is perfect. Case closed. We seemed to have identified the perfect data set… But just to be super sure, lets open the rasa shell and interact with the bot a bit.

rasa shell

Your input -> what is the price of this house

home data info

Your input -> my sister wants a motorbike

vehicle info

Your input -> whats the damage on a place like this

I'm doing great thanks

Your input -> what is the price of this car

home data info

It started off so well but went downhill quickly. To a human, the questions being asked may all seem similar but our model doesn’t have a complete vocabulary and certainly doesn’t understand all the nuances of English grammar. This is where our NLG program comes in. Enter my super simple dataset extender program - superfluous.

Please get to the point

By utilising the popular Wordnet database we can take a simple utterance as a base and create a number of similar sentences. This is done by analysing the sentence, removing stop words, and then taking the remaining nouns, verbs, adjectives and building a list of synonyms for each. Its then just a matter of applying a simple mathematical construct to the lists to generate the variants. Which mathematical construct? Our favourite of course - Carthesian product

In the field of mathematics, specifically set theory, the Cartesian product of two sets A and B, denoted A × B is the set of all ordered pairs (a, b) where a is in A and b is in B. Wikipedia just phrased that so perfectly that I don’t feel the need to explain further, but an example might help, given sets [A,B,C], [D,E] and [X,Y,Z] the carthesian product of those sets would be the following

ADX, ADY, ADZ, AEX, AEY, AEZ

BDX, BDY, BDZ, BEX, BEY, BEZ

CDX, CDY, CDZ, CEX, CEY, CEZ

Thats 18 sets. Three possible values for position 1, two possible values for position 2 and three possible values for position 3 (3 x 2 x 3 = 18) If we think of this in terms of our problem - we have a sentence with a number of verbs, nouns and adjectives, each with their own synonyms, having these parts of speech in our sentence multiplies the number of ways this sentence can be said by the number of synonyms.

Lets apply this to our problem, you can find my code here, but basically I’ve implemented two strategies, a simple strategy and an aggressive strategy. This code snippet shows the basic structure of the code. Use the github link to access the full code.

const WordPOS = require('wordpos');

const cartesian = require('cartesian');

const wordpos = new WordPOS();

const synonymsFilter = arr => { ... }; // clean the synonym data

const sentencesFilter = (arr, minLength) => { ... } // last pass clean of the resulting sentences

const writeToFile = (sentences) => { ... } // write our sentences to file

// use the function provided to get first definition from wordnet and use its synonyms

const simpleBuilder = async (fn) => {

const res = await fn();

return synonymsFilter(res[0].synonyms);

};

// use the function provided to get all definitions from wordnet and use all synonyms

const aggressiveBuilder = async (fn) => {

const res = await fn();

const masterSynList = [];

res.forEach(lookup => synonymsFilter(lookup.synonyms) // filter for good synonyms

.forEach((s) => {

if (!masterSynList.includes(s)) {

masterSynList.push(s);

}

}));

return masterSynList;

};

async function main(sentence, aggressive = false) {

const wordArray = sentence.toLowerCase().split(' '); // split our sentence into an array of words

const megaSentenceList = [];

for (let i = 0; i < wordArray.length; i += 1) {

const w = wordArray[i];

let fn = async () => [{ synonyms: [w] }]; // basic synonym list is just itself

if (!WordPOS.stopwords.includes(w)) { // don't bother swapping stop words

if (await wordpos.isNoun(w)) {

fn = async () => wordpos.lookupNoun(w); // function to lookup a given noun in wordnet

} else if (await wordpos.isVerb(w)) {

fn = async () => wordpos.lookupVerb(w); // function to lookup a given verb in wordnet

} else if (await wordpos.isAdjective(w)) {

fn = async () => wordpos.lookupAdjective(w); // function to lookup a given adjective in wordnet

}

}

if (aggressive) {

megaSentenceList.push(await aggressiveBuilder(fn)); // apply the aggressive function and add the sentence to our megaSentenceList

} else {

megaSentenceList.push(await simpleBuilder(fn)); // apply the simple function and add the sentence to our megaSentenceList

}

}

const cartesianProduct = cartesian(megaSentenceList) // get the cartesian product of our sentences

.map(a => a.join(' ')); // join each word array using a space

const filteredSentences = sentencesFilter(cartesianProduct, wordArray.length);

writeToFile();

}

const sentence = 'what price is this home';

main(sentence);

Using the simple strategy we create 8 variants a single home rental price utterance, and 22 variants of the car sale utterance. Our Rasa instance takes around 15 seconds to train on this data.

- what price is this home

- what price is this place

- what cost is this house

- what monetary value is this place

...

- My friend here would like a motorbike

- my brother would like a large auto

- my brother would love a big automobile

- my pal would like an oversized car

Using the aggressive strategy we create 136 variants of the home rental price utterance and 2552 variants of the car sale utterance. Our Rasa instance takes about 9 minutes to train on this data, and some of the utterances get pretty wild.

- what price is this home

- what cost is this domicile

- what monetary value is this abode

- what damage is this household

...

- My friend here would like a motorbike

- my comrade would like a large motorcar

- my sidekick would like a handsome railcar

- myself would be happy to receive a vainglorious automobile

Command line looks pretty good again. The f1 score is in the high 90s, but lets check the console again to be sure

rasa shell

Your input -> what is the price of this house

home data info

Your input -> my sister wants a motorbike

vehicle info

Your input -> whats the damage on a place like this

home data info

Your input -> what is the price of this car

vehicle info

Success !! Maybe?

So if like me, you have more questions than answers, then I would encourage you to play around rasa, build some datasets, think about how you would solve this problem, build some rules to implement your solution and see how it goes. I’d love to hear about it.

So does this mean that the more training samples the better? Not really. It depends on the number of intents and their similarities, but we can confidently say that 2 is not enough.

Can you have too many training samples? Probably. Again it depends, using this algorithm in its most aggressive form could easily get out of hand and result in a suboptimal amount of utterances and potentially overlapping intents, a comfortable middle ground will keep the intent training sets separate.

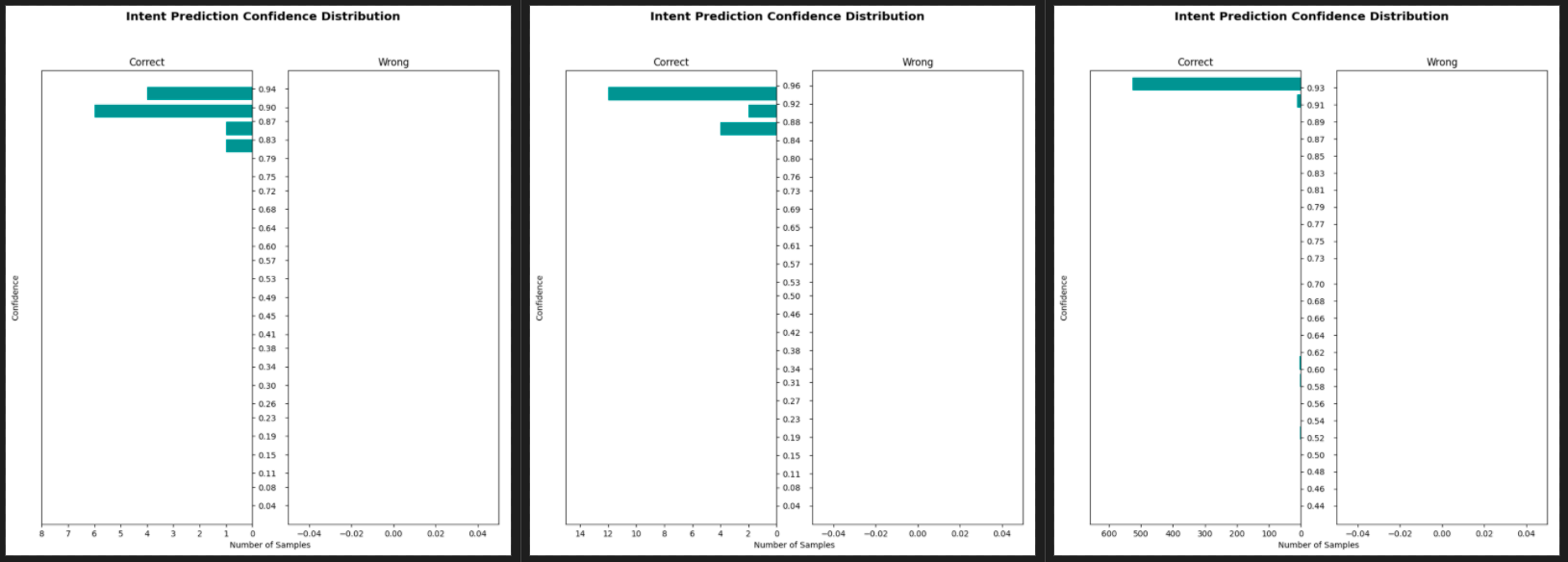

One other thing to note is the concept of diminishing returns and uneven distribution, adding thousands of training sets to one intent and not the other will more than likely skew your results. You can see from the charts below that as we increased the training set sizes for some intents and not others, that the confidence score starts to decrease dramatically for the intents with the smaller sets, our car based confidence score went from 90 to 96 to 93, but our greeting intent went from 87 to 92 to 53. Lots to consider.